A new study led by Kasun Kariyawasam (Gates Cambridge Scholar and PhD student at the Laing O'Rourke Centre for Construction Engineering and Technology, University of Cambridge) could be a real step forward in addressing the major cause of bridge failure.

What is believed to be the first-ever centrifuge test programme to show how sensitive bridges are to scour – the most common cause of bridge failure around the world – has been conducted by researchers at the University of Cambridge. The tests also found that bridges with deep foundations have higher frequency sensitivity to scour than those with shallow foundations.

Scour is the gradual erosion of soil around a bridge due to fast-flowing water and is thought to account for half of all bridge failures around the world.

Being able to reliably monitor it could help bridge engineers take timely countermeasures to safeguard against failure.

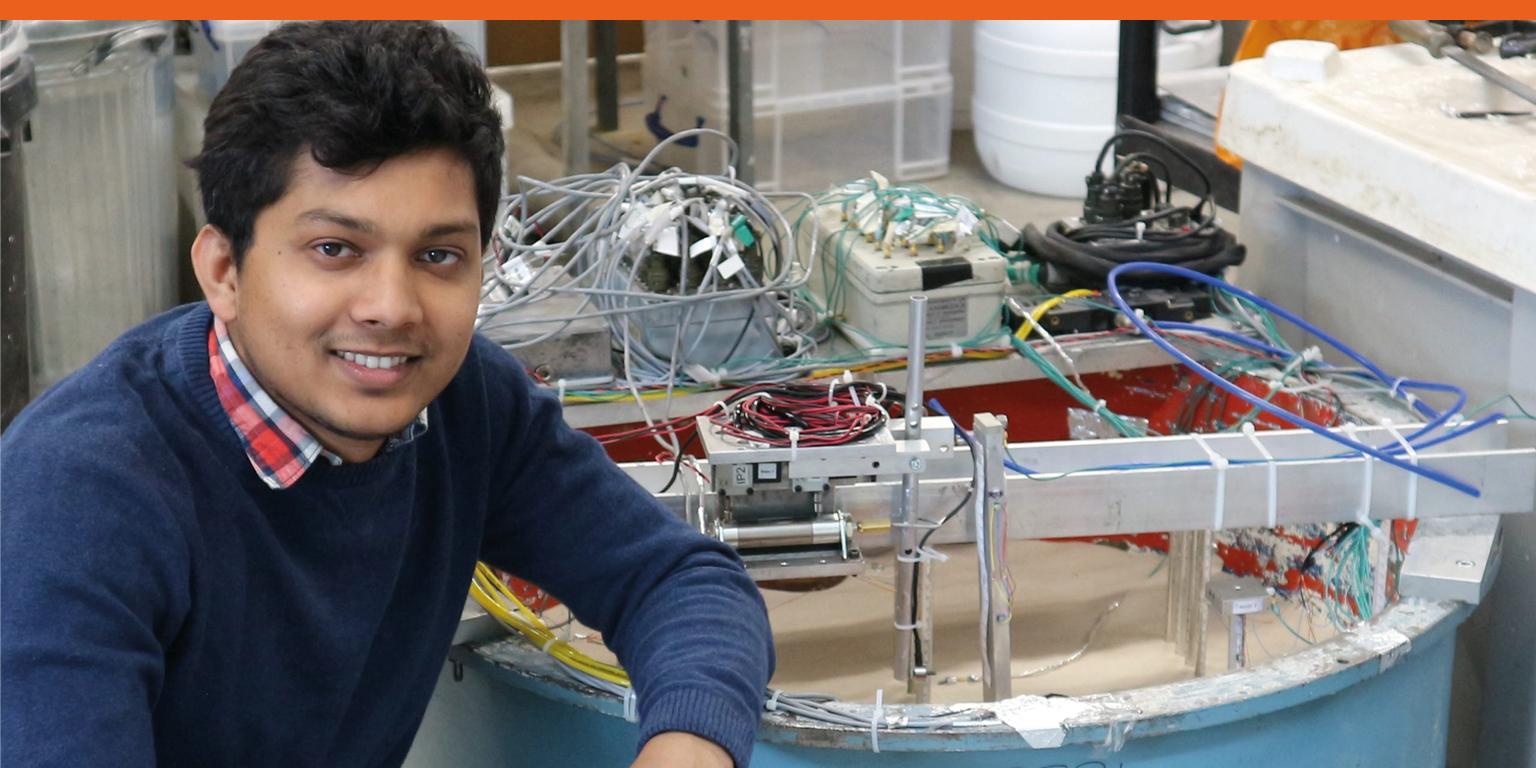

A paper published in the Journal of Civil Structural Health Monitoring lead-authored by Gates Cambridge Scholar Kasun Kariyawasam describes the development of what is believed to be the first-ever centrifuge-testing programme to establish the sensitivity of bridge natural frequency to different forms of scour in different types of bridges.

A 1/60 scale model of a two-span integral bridge with 15m spans was tested at varying levels of scour. Models of three other types of foundation were also tested in the centrifuge at different scour levels.

Kasun, who is doing a PhD in Engineering, said: “Most of the current techniques to detect scour have limitations related to cost, reliability and robustness and these limitations generally arise from the fact that the scour monitoring sensors have to be underwater. This research studied an alternative monitoring technique, which does not require any underwater sensor installations. It attempts to detect scour by tracking the changes in bridge vibration properties, such as natural frequency. This technique is very appealing because it is a real-time, remote monitoring technique.”

Another important finding is that the frequency sensitivity to “global scour” is slightly higher than the sensitivity to “local scour”, for all foundation types studied in this research.

Kasun says: “Such significant changes in natural frequency give new insights to bridge engineers and allow us to track natural frequencies of bridges to detect scour.”

Professor Campbell Middleton, Laing O’Rourke Professor of Construction Engineering at the University of Cambridge, who supervised Kasun’s research, said: “Scour of bridge foundations is by far the most prevalent cause of failure of bridges around the world yet, to date, no practical and effective monitoring technique has been devised to give advanced warning of the risk of impending collapse. Various researchers have tried using natural frequency based techniques to detect damage in bridges. However, these have tended to focus on identifying specific local defects, such as cracks or corrosion, and have met with very limited success.

“The technique examined in this paper focusses on characterising changes in the global vibrational response of a bridge due to the loss of soil around piled foundations as a result of scour. Our experimental centrifuge testing programme observed variations in natural frequency of up to 44% as a result of scour which indicates that this approach could, for the first time, provide a predictive tool for warning of impending scour failure in bridges built on piled foundations. This would be a very significant step forward in ensuring the safe operation of our bridge infrastructure.”